Ms. Briana’s preschool classroom is abuzz as children explore the room and engage in self-directed play. The room is organized into activity centers that are filled with a variety of materials to inspire them. Each child has their own unique interests, skill sets, and cultural experiences, which Ms. Briana takes into consideration when planning.

Today, her intentional planning efforts are on display: Harrison is playing with cars and blocks along with a few classmates, Maria, Tyson, and Khadija. Through previous observations, Ms. Briana has noticed that Harrison usually plays with the cars by himself. This week, she strategically placed a basket of cars in the block area, where other children play often. This small but impactful shift helps to support Harrison’s socialization, communication, and cooperative play.

Children enter preschool with a variety of knowledge, experiences, and abilities. As part of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP), early childhood educators are called to individualize their teaching strategies and curricula to meet these specific needs and contexts.

But what does this look like in practice? How do teachers intentionally plan learning experiences that build on children’s individual strengths? Following, we (the authors) outline ways that educators can identify children’s unique strengths and abilities, then offer examples of individualized lesson plans for different times and activities during the day. We base these practical planning recommendations on our past experiences—both of us worked in general and special education preschool settings for over 15 years and used similar planning tools. Currently, we are university professors working with pre- and in-service preschool teachers with whom we share these approaches.

DAP calls for educators to develop learning experiences that reflect both what is known about young children in general and about each child in particular. To do this, teachers must understand each child’s abilities, characteristics, interests, and contexts. Observation and building relationships with families are key ways to do this.

Observation is crucial during the learning day. It provides educators with meaningful information that may not be shared by families or children, and it offers insights into children’s strengths and preferences. For example, when a preschool educator spends time observing children’s language skills across different content areas and learning activities, they can start identifying ways to build on each child’s strengths and to meet their needs: A child with strong communication skills may need additional opportunities to express their thoughts and ideas (such as creating and sharing stories, role-playing in the dramatic play area, or discussing their work and play in detail). A child who has difficulty communicating in certain modes may need supports, such as picture cards to share their wants and needs, time to practice gestures or signs, or opportunities to engage in back-and-forth exchanges with adults and other children.

When observing, educators can look for and record a variety of skills and characteristics. Some of these may be easier to identify (physical abilities, language, food preferences); some may be more difficult (feelings and emotions, thought processes, culture). Educators can gather vital information by carefully watching and listening each day, in different areas and at different times. To gather meaningful data, they can use a variety of formal and informal techniques, such as running records, anecdotal notes, checklists, and time and event sampling.

To build on each child’s assets, it’s crucial that educators connect with families. By building these relationships, teachers will gather insights into children’s individual qualities and interests and their home and cultural contexts. This information is key to recognizing each child’s unique strengths and to providing a safe, comfortable, and responsive learning environment.

Preschool educators can tap families’ expertise in a variety of ways to strengthen school-to-home and home-to-school connections. At the beginning of each year, for example, Ms. Briana sends home a “Get to Know Me” page for families to share information. She also reaches out by phone or text to share positive observations about a child’s first week of school and to invite families’ initial questions and thoughts. Besides showing her genuine interest in building reciprocal relationships, these steps guide Ms. Briana as she sets up the learning environment and interacts with each child.

Throughout the school year, Ms. Briana continues to build relationships with families by sending home daily notes that include individualized examples of what their children did that day. She uses small, premade sheets with each center listed. She circles which centers the child participated in that day. The sheet also has blank spaces where Ms. Briana can record the day’s snack and the child’s favorite activity. She uses snack time to talk with each child and quickly fill out the form. These notes let families know that Ms. Briana checks in with their children individually each day.

Ms. Briana continues to make connections by email, text, and phone calls to share details about children’s learning and to help work through any issues if necessary. She uses family-educator conferences for more in-depth conversations, offering different days, times, and formats to accommodate families. She uses all of these points of contact to inform her intentional planning.

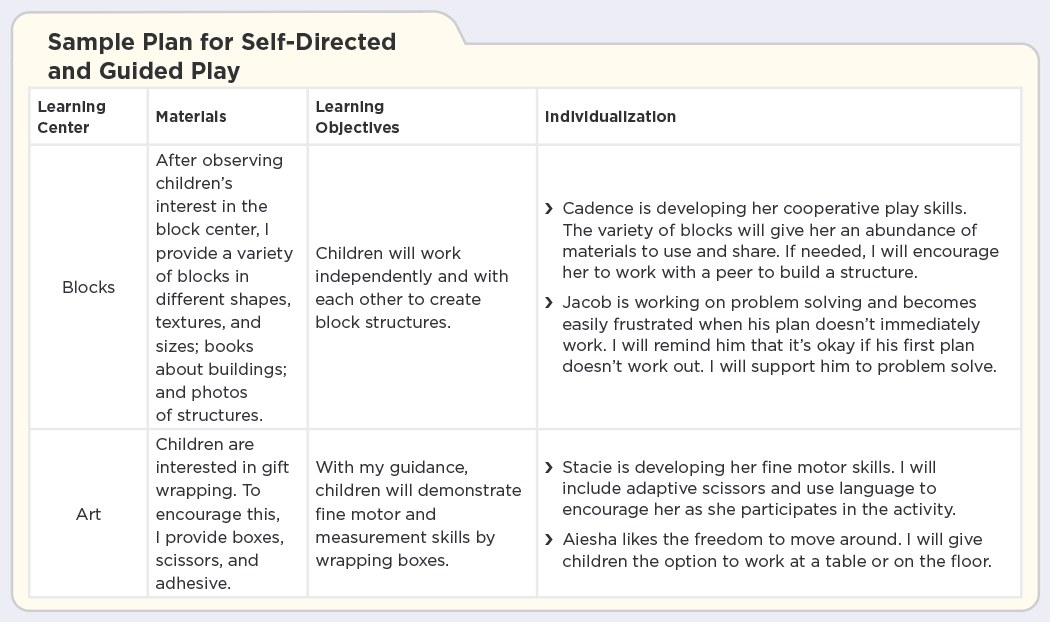

As they gather information about each child, educators can begin individualizing their plans for learning experiences. Rather than focusing on a particular activity or routine, this individualization should encompass the entire learning day—self-directed and guided play, small- and large-group experiences, and routines and transitions. Following, we offer some examples of planning for individualization.

Preschool settings should be intentionally created to nurture and support play and to address each child’s unique interests, strengths, and needs. Educators can do this by rotating a variety of materials and toys that children are interested in. These should represent different races, cultures, genders, family structures, and other aspects of identity.

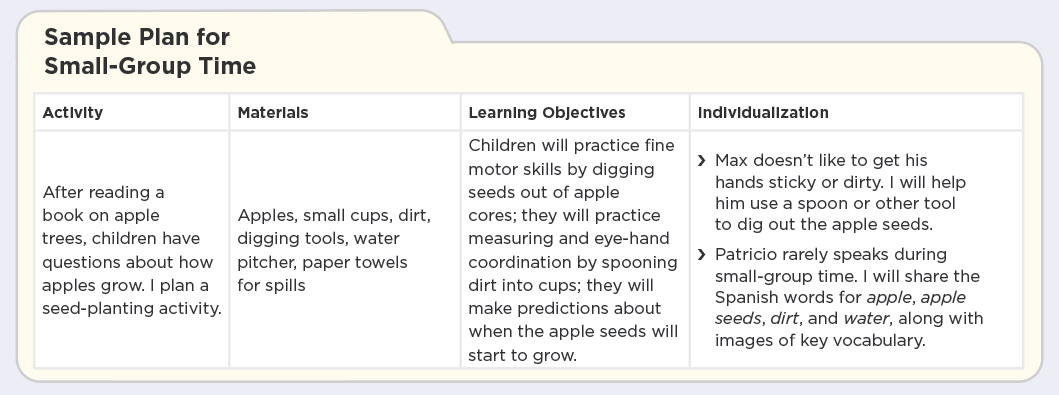

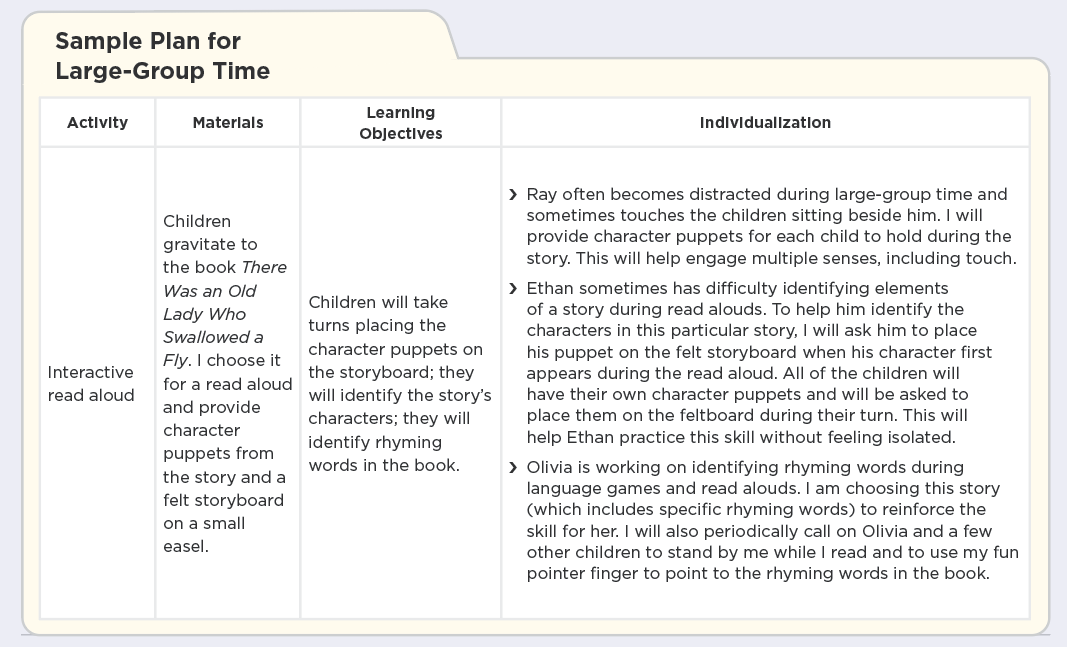

When children work in groups, they share their individuality and learn from their peers. Educators can scaffold small and large gatherings by planning activities that build on children’s interests and assets and that encourage them to share their experiences, thoughts, and feelings as they work together.

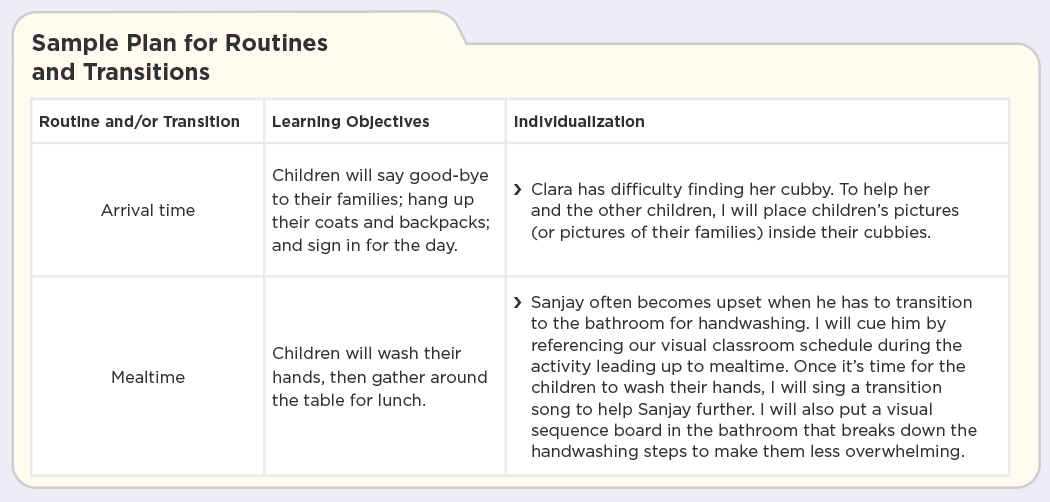

Routines (arrival, mealtime, transitions from one activity to another) are an integral part of preschool. During them, children practice many developmental and learning skills. For example, children work on social skills at snack time by waiting their turn; they practice their language and communication skills when they ask for a snack.

At the same time, routines can challenge children who are still developing specific skills. Educators can capitalize on these moments to individualize and scaffold instruction, tapping into children’s strengths and addressing their individual areas for growth.

Planning for each and every child in an early learning program is an ongoing process that requires continuous commitment. By honoring each child’s unique strengths and abilities, early childhood educators position individual children for success as they celebrate all of the children and families in their settings.

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 1: Relationships

1A: Building Positive Relationships Between Educators and Families

Standard 3: Teaching

3E: Responding to Children’s Interests and Needs

Standard 4: Assessment of Child Progress

4E: Communicating with Families and Involving Families in the Assessment Process